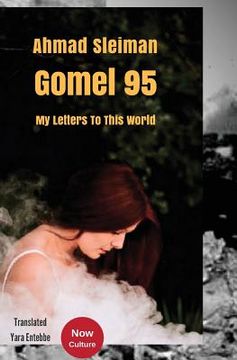

Gomel 95 / my letters to this world (A special English version of Now the center of culture)

Synopsis "Gomel 95 / my letters to this world (A special English version of Now the center of culture)"

T HEY NAMED ME Ahmed. It indicates a clear trend. I realized that when the Mufti slapped me because I wanted to change it. O' great-grandfather, I think I'm your grandson. I was a child named Orhan, then Amjad. There is a mistake in your records. Ahmed who is on the ID is four years younger than I! I am a mistake in the State's records; my age is just on a card, my health is getting worse, and my father only remembered my real name one Eid morning in a cemetery and I forgot how my shape used to look like. I'm still wearing the political suspicion. And I still remember my father's features when the family said its last farewells to him. At that time, the illusions of parties and our furious anger pushed us violently. My father and I left, but he left before me. His destination though is different. He remains in his tomb while I destroy myself regularly as if I'm building my own tomb. I leave my pictures and newspaper clippings with my two little ones. I left them while they needed me more than anything in the world. I asked my father before his departure: "In what way do you pray?" The storyteller is more silent than I. He didn't conceal his support when I asked about the feasibility of a cultural project that is surging in this golden age. I didn't find convincing answers, so as usual, I rave when I see no authority bearing the moods and tendencies of poets in this vast world; its vastness is not enough for angels of language and mercury that wear sanctity and knowledge. Another truth, nay, truths wrapped in hazy memory like the woman who never learned to utter my name. She left but her question keeps murdering me every moment; the question that led me to read the world and those whom I love again. Trotsky was my grandfather. He doesn't know me but I'm his clone. Thus, like many of my fellow countrymen, I carried life on my shoulder. I conceal some protest memoranda among my school books. Little did my father ask me about the purpose of those papers. I read them with utmost sincerity while life took a different direction. Alone, one woman was leading us to the light, coming out of book pages to our consciousness which resembles the revolution dream. There wasn't a reason for women to do our tasks. But they are women; they think of speeches and statements that pierce the dreams of yesterday's children, for they no longer look like us. We were all busy talking about the searing revolution as if it were going to outbreak. All of us were following the woman who would lead us to the light. We were in a blind world thinking of the other, hating lazy leaders. That woman resembles us. We stand behind her as a perpetual symbol. Her name is Rosa Luxemburg. We were the ones who hated the leaders. They put in their eyes more than a veil as Federico Garcia pointed out in a sentence read by the governor of Granada from a newspaper clipping that Funisca, the mastermind of the murder of Lorca, found. We loved Lorca for his transparent language. We also differ with a man who made his mustache the enigma of the speedy age. This man is Salvador Dali. He only signed the works of students who imitated his work. He alone agreed with Federico Lorca and stabbed his senses in one of his letters that put an end to a relationship based on knowledge and art in a culture palace. As usual, under the pretext of jealousy that some of Pablo Neruda and Nazim Hikmet poems require, and some writings about the renewable revolution and the conflicts of Trotsky with the Kremlin leaders. We never grew tired of this news. They are also about the magic that André Breton's view of Surrealism enchants. We haven't read Iloar and Arthur Rambo and Aragon because there was something pulling us to revolution poems until the revolution died in us, and the dream remained a symbol of hope and another revolution.